The Ghost Tracks

On some days at Higbee Beach (or nights, if you’re feeling brave — it’s spooky out there), the Delaware Bay does a magic trick. You walk the sand like you always do — wind in your face, gulls arguing overhead, a ferry boat off in the distance — then the beach changes. Out of the wet sand, a set of rusted rails and heavy wooden ties appears like the shoreline is briefly remembering an old dream.

We call them the ghost tracks, and they don’t show themselves on a schedule. They come and go on the bay’s terms: storms, erosion, low tide... and who knows what else.

As elusive as they appear to be, we can actually pin down when these tracks have popped up in modern times, because photographers and reporters have been chasing them like rare birds.

November 2014: A major reappearance, with media reports stating that the rusted tracks appeared magically and hadn’t been visible since the 1930s.

March 2018: Back-to-back storms unearthed them again, prompting stories in the Associated Press and The Weather Channel.

January 2021: A nor’easter and shifting sands brought them back.

May 11, 2022: Coastal storms and low tide revealed them again — an event widely documented, including detailed reporting by AccuWeather.

Since then, the tracks have appeared multiple times again, provoking another tranche of compelling, spooky photos to appear on social media.

But here’s the thing... that whole “first appearance in 80 years” claim simply isn’t true! Back when I had dogs (there were four mutts during one particularly mad, and wonderful, time), I saw the tracks on several occasions. The first time would have been the winter of 2004-05. I know this because my pups, April and Friday, were less than a year old at the time and they came into this world in March of that year. Being an excellent dog daddy (and someone in need of exercise), I walked my pups on Higbee Beach twice a day, every day. So whatever weird things were happening on Higbee (from stubbornly naked beachgoers to the disappearance of the Voodoo Tree to ghostly train tracks), I was usually there to witness them.

I thought the appearance of those rusty old tracks was cool, but I didn’t make a big fuss about it — partly because there was no social media on which to make a great fuss! I think I briefly mentioned it in my Ramblings column in this magazine and do recall a couple of people not believing me. But I never thought about it that much again, until the appearance of the tracks in 2014 started to attract crazy traffic to the parking lots at Higbee and Sunset Beach. (The moniker of “ghost tracks” probably helped pique people’s interest.)

So, yes, the beach is doing what beaches do — moving, eroding, reshaping. But what it’s revealing is something most people don’t expect to find at the edge of Cape May: a piece of early-20th-century industry.

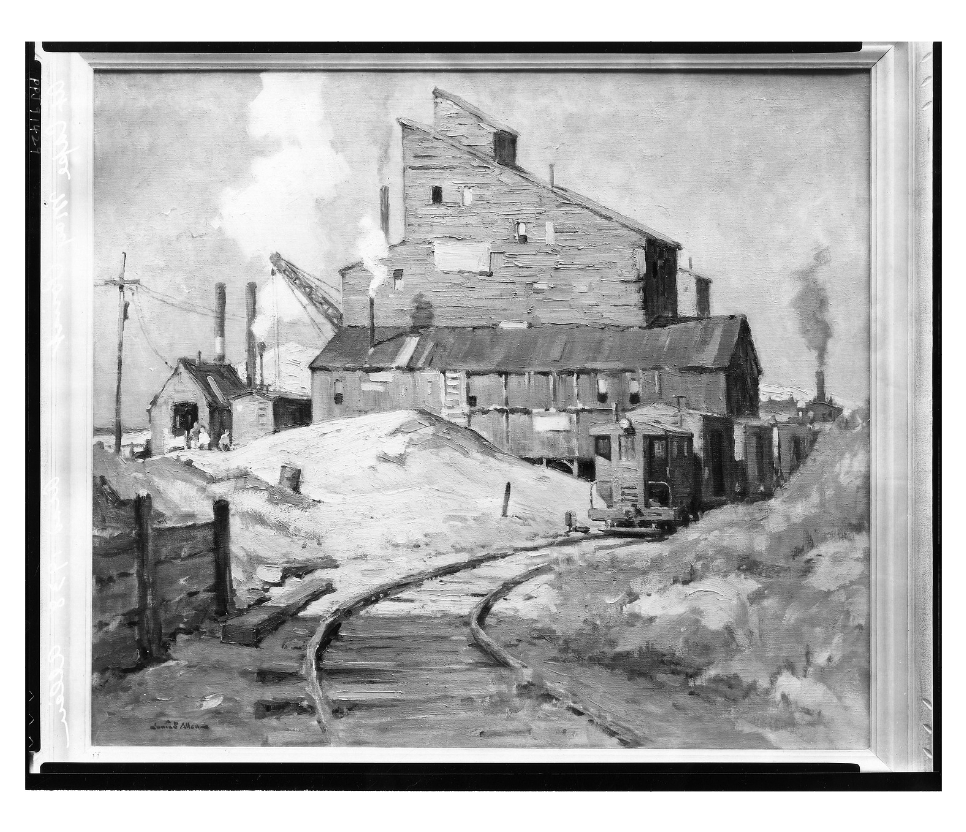

So where exactly did the tracks come from? The story begins with a business name that sounds almost too plain to be important: the Cape May Sand Company, which began life in 1905 and provided sand for construction, using a beach-and-bayfront operation where sand was scooped up, washed, and then loaded into train cars. Those cars ran along the beach and into Cape May’s winter station to be shipped north.

The tracks linked up to the Atlantic City Railroad (aka the Royal Route to the Sea), which connected AC to Philadelphia.

The sand mining and dredging continued after World War I, with sand processed for glass and cement products — but the city suspended the operation in 1936 due to concerns about depleting sand on bathing beaches.

But there’s more to the story than simple sand. The tracks are also tied to Bethlehem Steel — specifically to munitions testing during World War I.

Eugene Grace, a Goshen native who would become president of Bethlehem Steel, established several ordnance testing grounds in this county. One of those grounds extended from Higbee Beach north along the bayfront toward Reed’s Beach, 16 miles up the coastline in Middle Township.

Ammunition was brought to Cape May by train, trucked to Higbee, then carried to firing areas on the beachfront by small-gauge trains. The rail lines along the beach were used to transport munitions and cannons along the coast of what is now the wildlife management area.

After Cape May Sand Company left the picture in 1936, a magnesite plant was built on the site. The plant mixed salt water extracted from the bay with lime to create a magnesium solution that was used for the production of fire bricks. The magnesite plant closed in 1983 and has remained an eyesore ever since but, thankfully, is being absorbed into the Higbee Wildlife Management Area restoration project, into which $37.5 million is being poured by New Jersey’s Department of the Environment.

So if you’re standing on Higbee Beach looking at those rails, you’re not just seeing an old train track on a beach. You’re looking at the physical footprint of a period when Cape May County was doing industrial work in service of war —and doing it right on the sand.

Cape May has a well-earned reputation for gingerbread trim and beach days, but it has always had another identity too: a working coastline where the national story shows up in very local ways.

Or, to put it another way, the bay rearranged the furniture again.

One of the joys of this story is that it keeps becoming real-time news — history surfacing into the present.

In 2022, historian Ben Miller, author of our best-selling history book, The First Resort, described the tracks as “like hidden treasure,” adding that “all of a sudden they’re there... like a portal to the past.”

That’s the pattern: a storm happens, the tide cooperates, someone gets tipped off, and suddenly the beach is hosting a pop-up museum exhibit — open for a few hours, then gone.

As for that big fancy restoration project, the DEP has said that “the majority of the ghost tracks will remain in place,” but portions encountered during restoration work may be removed, cut, and stockpiled “for future interpretive use by the State.”

So, although the ghost tracks may keep doing their disappearing act over the years, a small part of the story may eventually be preserved in a way that doesn’t depend on the perfect storm.

In the meantime, conditions are pretty ghost-track friendly. Once the temperature rises above freezing, fill your flask with coffee, charge up your iPhone and get out there to record history. But take a minute or five to enjoy the moment before blowing up your social feed. It’s beautiful out there (and thankfully way too cold for nudists).

Artist Junius Allen painted this scene of Cape May Sand Company in the 1930s.

Liz Goldsmith shot the ghost tracks in 2022.

They appeared again in November 2024.