The Inferno That Changed Everything

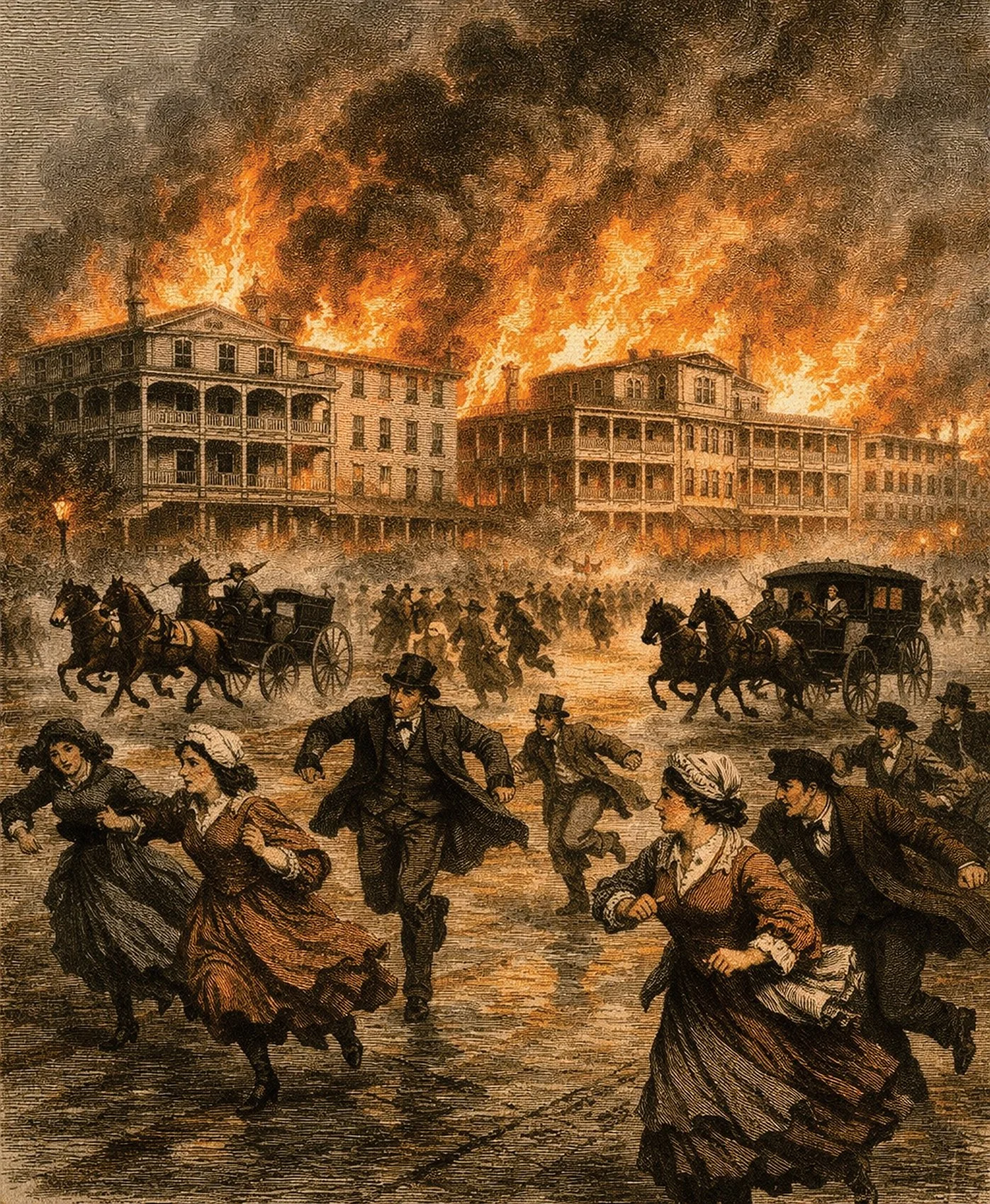

Some time around seven o’clock on the morning of November 9, 1878, workmen on the roof of the Stockton Hotel saw smoke coming from the Ocean House on Perry Street, across from Congress Hall. Soon after, Colonel Henry Sawyer, owner of the nearby Chalfonte Hotel and Cape May’s most celebrated Civil War hero, raised the alarm.

Within an hour, church bells were ringing all over town to alert the people, but Cape May never stood a chance: its entire fire-fighting apparatus consisted of a single hand engine, 1,500 feet of rubber hose, three chemical units (which mixed water, baking soda and acid to produce foam) and a hook-and-ladder truck.

A train was dispatched from Camden, 90 miles away, with a steam engine and a supply of hose, but by the time it arrived, four hotels were ablaze. Fanned by a 35mph wind from the west, the fire spread further east, and soon the Columbia House hotel was ablaze. By the day’s end, nearly 40 acres of beachfront property had been destroyed.

The Cape May Wave reported that there had been hope of saving Congress Hall — “the strong probability is that with a moderate supply of water it would [have survived], but for the unfortunate bursting of the hose just as the engine had got fairly started. Another section of hose was put in place of the one injured. That also burst... Finally, after some five sections of hose had burst in the same way, the flames in the meanwhile traveling with astonishing rapidity under the roof on the ocean front, Congress Hall was relinquished to its fate.”

Although Congress Hall’s owners might not have agreed with the sentiment, the Wave went on to say that “Congress Hall as it burned presented a magnificent scene from the beachfront, the flames pouring out from its hundred windows, enveloping balconies and verandas, leaping into the air a hundred feet, and making a noise like the thundering of a score of express trains over a wooden bridge.”

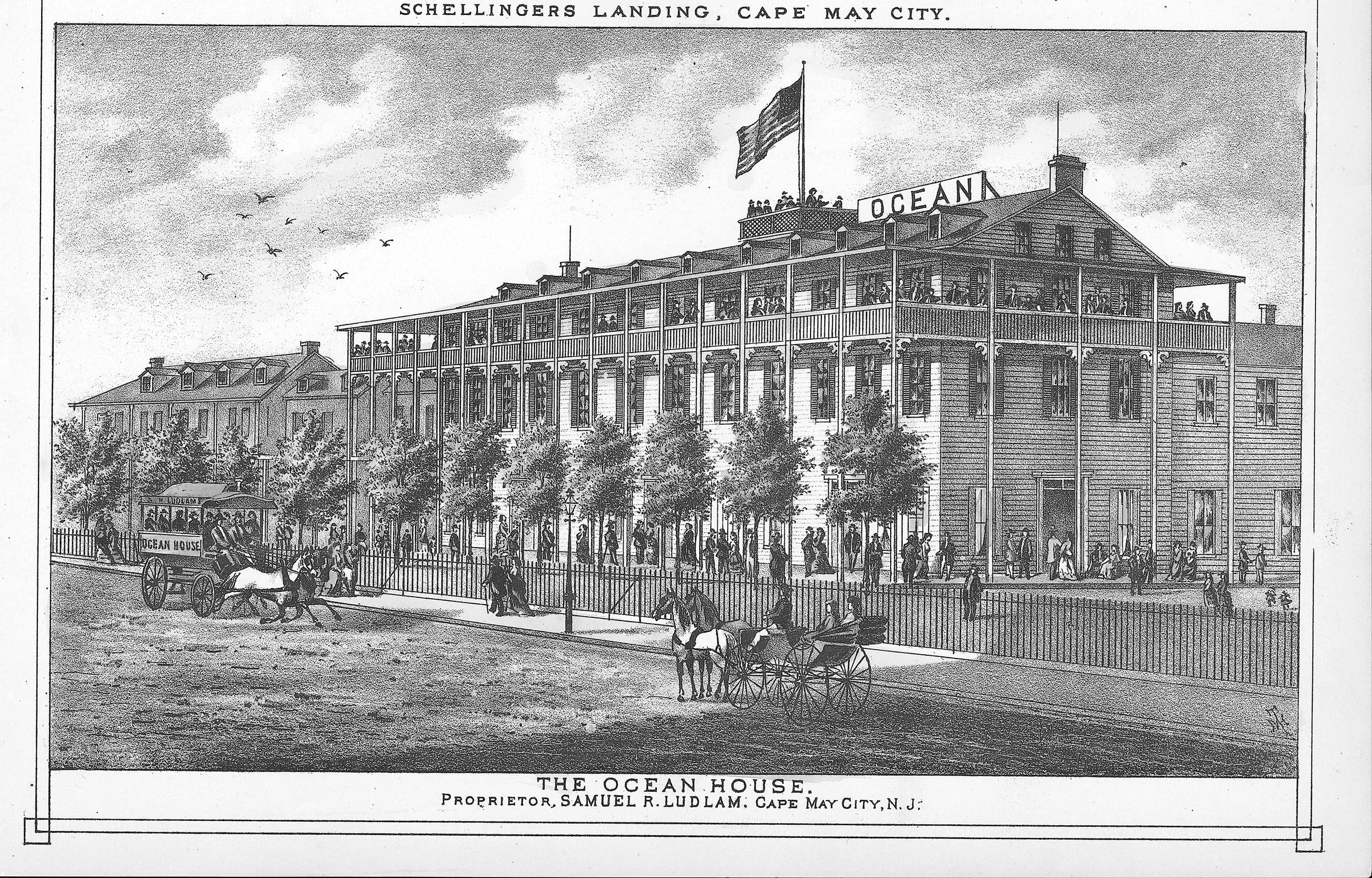

The cause of the fire, which had come just two weeks after an 84mph gale had sheared off a huge chunk of Congress Hall’s pier, was determined as arson. Samuel Ludlam, proprietor of the Ocean House, was charged and taken to trial, but was found not guilty. (Remarkably, no lives were lost.) The city council, though, was held accountable by many for the quick spread of the inferno.

“So highly inflammable a town as Cape May ought to have been especially well provided with engines and hose, but Cape May appears to have been scarcely provided at all and the inhabitants evidently were utterly untrained in the duties of firemen,” opined the The Evening Telegraph of Philadelphia offered some hope to the city: “If those who have the most positive interest in maintaining the well-won reputation of the place as a peculiarly agreeable summer resort will go to work with energy and intelligence to repair the damage that has been done, and to make it in the matter of elegant and comfortable accommodations, more than ever worthy of the regards of summer loiterers, it may turn out that the fire of Saturday was a blessing in disguise.”

The Philadelphia Times added, “There is a silver lining to every cloud, for as many of the buildings destroyed were old and dilapidated, neater and more substantial modern structures will raise upon their sites.”

Congress Hall’s future, though, wasn’t looking too assured in the aftermath. Two weeks after the inferno, the Wave reported that the hotel would not be rebuilt.

In the same issue, the newspaper’s editor clearly felt his readers were in need of some humor to relieve the mood of foreboding and uncertainty that was clinging to the town. Here was how one of the newspaper’s writers lampooned the raging debate in town as to how Cape May, and in particular its most famous hotel, should rebuild: “Congress Hall has been purchased by immensely wealthy people. Bonanza people. Who intend to build, not for the purpose of making money, but for the sole purpose of benefitting and pleasing others, as such people invariably do. A hotel is to be built capable of accommodating all who can pay a good price for very little. It will be entirely fireproof, especially against bed bugs and cockroaches... It will be elevated 100 feet above the ground on an immense turntable, which will be made to revolve by a powerful engine worked by an imported organ grinder. The building will be 900 feet wide and 2,105 feet 0.75 inches long, built on the telescopic plan, so that it can be reduced or enlarged as required. When extended to its full size it will shade the city in a hot sunny day or protect it from the rain, thus ensuring to us a climate that even Atlantic City cannot find fault with. As the hotel revolves, each room will have a sea view.”

That’s some funny stuff!

“For any loss that they have suffered they will get little sympathy, but they ought to learn from this that if they expect capitalists to build hotels in their town — and without hotels there would be no town — they must make some effort for their protection.”

Cape May’s fire chief, Edward Lansing, admitted that the city was ill-equipped to handle a blaze of this magnitude. He helpfully added that his request earlier that year for funds to purchase new equipment had been denied by city council because of budget constraints. (Not surprisingly, council readily approved the funding for new equipment at its next meeting.)

It was widely assumed that Cape May would rally around a huge effort to rebuild and modernize the resort in a bold attempt to challenge the ascension of Atlantic City, the resort that had been created in 1854 by a group of Philadelphian bankers who wanted a resort closer to home, and which had already usurped Cape May as the state’s premier resort town.

But Cape May didn’t rebuild to anything like the scale of the hotels which had burned. Here’s why: Major developments in the town had fallen under the control of a small group of Philadelphia businessmen who had remained loyal to Cape May when many others had left for Newport, Rhode Island, which had become America’s playground for millionaires.

The Philadelphian movers-and-shakers who stayed were keen to curb Cape May’s growth, content for it to regress to the state of a quiet seaside resort where they could take their summer rest, far from the bustle of Philadelphia and the boom town of Atlantic City.

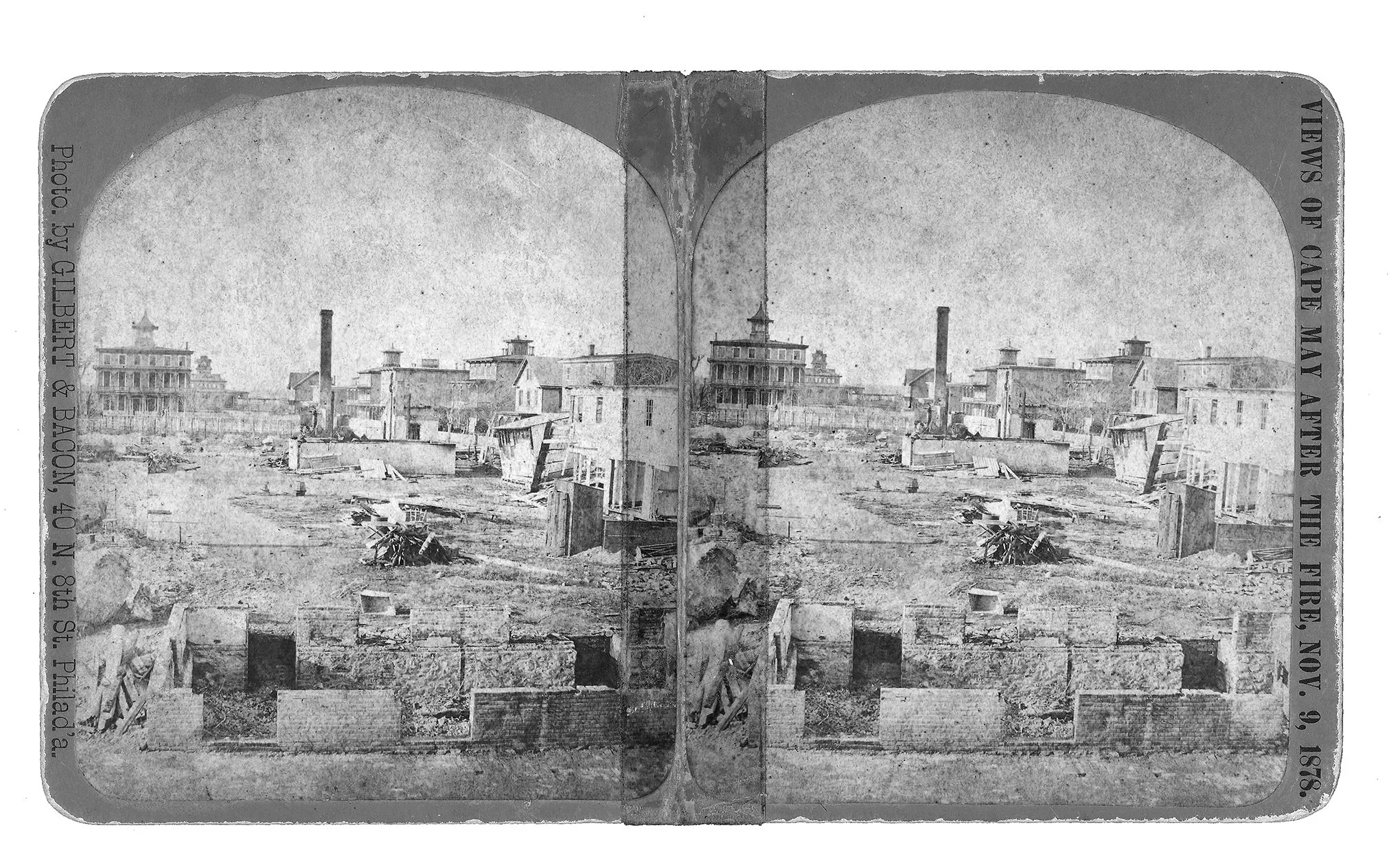

Congress Hall was rebuilt, with brick, but at less than half the size of what came before (and it was originally painted sage green — yellow didn’t come until 1884). The other major hotels that were destroyed were replaced by smaller private homes, featuring ornate gingerbread rim and turrets.

Many of these post-fire properties formed the collection of Victorian buildings that allowed a historic preservation expert to get the city named as a National Historic Landmark almost 100 years after the fire broke out — but that’s a story for another day.

The 1878 Disaster That Transformed Cape May

The fire began in the Ocean House, now the site of the Star Inn and Carpenter’s Square Mall.

A stereoscopic image shot by Gilbert and Bacon shows the aftermath of the 1878 fire. This wasteland was occupied by the old Congress Hall.